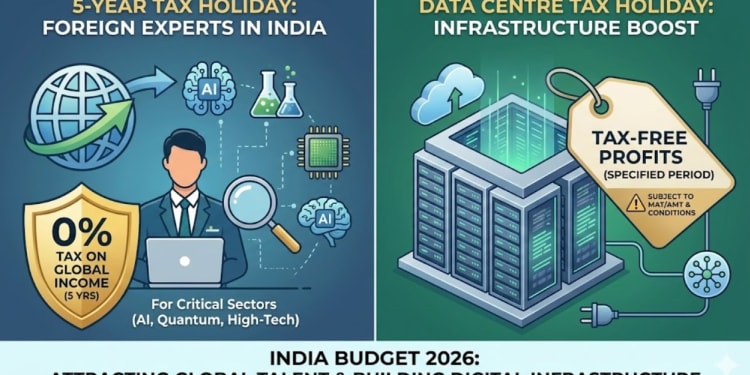

Budget 2026: 5-Year Tax Holiday on Global Income for Foreign Experts in India and Analysis of the Data Centre Tax Holiday

Budget 2026: 5-Year Tax Holiday on Global Income for Foreign Experts in India and Analysis of the Data Centre Tax Holiday

Part A: Tax Holiday on Global Income for Foreign Experts in India

In a strategic move to position India as a global hub for high-end technical expertise and innovation, the Finance Minister, in the Budget 2026, has proposed a significant tax incentive for foreign experts. Amidst the backdrop of the recent India-EU trade negotiations and the push for "brain gain" and “talent exchange” the government has introduced a specific exemption in the Income-tax Act, 2025.

This new provision allows eligible foreign experts visiting India to keep their global income (income accruing or arising outside India) tax-free in India for a period of up to five years, provided they are working under a notified Government scheme.

The "Tax Certainty" Problem

Under the general residence rules of Indian tax law (specifically Section 6 of the Income-tax Act, 1961, and carried forward to the 2025 Act), an individual's tax scope expands based on their physical presence in India:

- Non-Residents are taxed only on Indian-sourced income.

- Residents (ROR) are taxed on their global income.

Foreign experts visiting India for long-term projects often face the risk of becoming "Resident and Ordinarily Resident" (ROR) due to their extended stay, thereby exposing their worldwide income (rental income abroad, foreign interest, capital gains, etc.) to Indian taxation. This has historically been a deterrent for top-tier global talent.

The 2026 Proposal:

To resolve this, the Finance Bill 2026 proposes an insertion entry number 13B in Schedule IV (read with Section 11) of the Income-tax Act, 2025.

- The Benefit

The exemption applies to "Any income which accrues or arises outside India, and is not deemed to accrue or arise in India." This ensures that while the expert pays tax on the salary earned for services rendered in India (which is Indian-sourced), their passive or active income earned outside India remains untouched by the Indian tax authorities.

- Eligibility Criteria

To qualify for this exemption, the individual must meet strict criteria designed to ensure the benefit targets genuine foreign talent:

- Non-Resident History: The individual must have been a non-resident for five consecutive tax years immediately preceding the year they visit India.

- Purpose: The visit must be for rendering services in connection with a scheme notified by the Central Government.

- Duration (The Sunset Clause)

The exemption is time-bound. It is available only for a period of five consecutive tax years, commencing from the first tax year in which the expert visits India for the notified scheme.

Strategic Implications and Historical Context

This move effectively revives and modernizes older incentives that existed under the Income-tax Act, 1961, such as:

- Section 10(6)(vi): Exempted remuneration of foreign employees of foreign enterprises for short stays (90 days).

- Section 10(8) & 10(8A): Exempted global income of individuals/consultants working under technical assistance programmes with foreign governments or international organizations.

- Section 10(6)(viia): Previously provided exemptions for foreign technicians.

The 2026 scheme, however, is broader in duration (5 years) but stricter in scope (linked to specific notified government schemes). This likely targets sectors like semiconductors, green hydrogen, and advanced AI, where India seeks knowledge transfer—potentially aligned with the exchange of expert knowledge clauses in trade deals like the India-EU agreement.

The Disclosure Dilemma

While the proposal is quite attractive for global talent, it remains silent on the critical aspect of the disclosure of Foreign Assets by such individuals during their five-year stay. This creates a potential compliance paradox. Under the new proposal, the expert's global income is explicitly exempt from tax in India. However, by staying in India for five years, the expert will likely become a "Resident" under Section 6 of the Act. Under the Income-tax Act and the Black Money (Undisclosed Foreign Income and Assets) and Imposition of Tax Act, 2015, a "Resident" is mandatorily required to disclose all foreign assets (including bank accounts, financial interests, and immovable property) in the Income Tax Return (Schedule FA).

Technically, even if the income is exempt, the status of being a Resident triggers the reporting obligation. Failure to disclose these assets can attract severe penalties of ₹10 lakhs or more under the Black Money Act, even if no tax is payable on the income generated by those assets.

It is hoped that the Government will issue a specific clarification or notification to exempt these experts from the rigorous reporting requirements of Schedule FA and the Black Money Act. Without such clarification, foreign experts may still face the heavy compliance burden of disclosing sensitive global asset details to Indian authorities, despite their income being tax-exempt.

Part B: Analysis of the Data Centre Tax Holiday

Further, the Finance Act, 2026 has introduced a specialized tax regime for the data centre ecosystem. Recognizing data centres as "critical infrastructure," the Hon'ble Finance Minister has proposed a dual incentive structure: a tax holiday until 2047 for foreign cloud service providers and a Transfer Pricing Safe Harbour for Indian infrastructure providers.

This move is codified through the insertion of Entry 13C in Schedule IV (read with Section 11) of the Income-tax Act, 2025, exempting specific income of notified foreign companies derived from procuring data centre services in India.

The Proposal:

The exemption effectively insulates foreign cloud providers from Indian income tax liability on their global income routed through Indian servers, provided specific conditions are met.

- The Benefit

- Income Exempt: Any income accruing or arising in India (or deemed so) by way of procuring data centre services from a specified data centre.

- Sunset Clause: The exemption is available for tax years ending up to 31st March, 2047.

- The Conditions

To qualify, the foreign company must adhere to strict operational boundaries:

- It must be notified by the Central Government.

- The foreign company must not own or operate any physical infrastructure or resources of the specified data centre. This is crucial to avoid the characterization of a "Fixed Place Permanent Establishment" under domestic law.

- All sales to users located in India must be routed through an Indian reseller entity.

- Mandatory maintenance and furnishing of prescribed information.

Analysis: Context of Significant Economic Presence (SEP)

The introduction of this scheme creates a specific statutory carve-out from the rigorous "Significant Economic Presence" (SEP) norms codified in the Income-tax Act. Under Section 9(1)(i) (specifically Explanation 2A), a non-resident is deemed to have a business connection in India if they have a Significant Economic Presence. This is defined by:

- Transaction Threshold: Payments exceeding ₹2 crores from Indian users for goods, services, or data/software downloads.

- User Threshold: Systematic soliciting of business or engaging with 3 lakh+ users in India.

A foreign company hosting data in India to serve global and Indian clients would invariably trigger SEP due to the high value of data transactions and digital interaction with Indian users. Furthermore, under the Source Rule, income attributable to infrastructure located in India is typically taxable.

However, Entry 13C overrides Section 9 by exempting the income entirely. By mandating that Indian sales go through an Indian reseller, the government ensures that revenue from Indian customers is taxed in the hands of the Indian reseller, while the foreign company's income from global customers (using Indian infra) remains tax-free. This effectively decouples the "infrastructure location" from the "taxing right" for global revenues.

Context of Treaty Network (DTAA) and "Server PE"

The scheme addresses a long-standing jurisprudential debate regarding "Servers" as "Permanent Establishments" (PE).

Under Article 5 of most Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAAs), a PE includes a "fixed place of business."

- International Position: The OECD commentary often distinguishes between a website (intangible) and a server (tangible). A server owned or leased by a foreign enterprise and at its disposal can constitute a Fixed Place PE.

- Indian Position: India has historically reserved its right to treat a website or a server located in India as a PE if it leads to significant economic activity. If a foreign company owns servers in India or leases them under terms that give them effective control/possession, it risks constituting a Fixed Place PE

By explicitly requiring that the foreign company does not own or operate the physical infrastructure (Condition 'b'), the scheme strengthens the argument that the foreign company does not have a "fixed place of business" at its disposal in India. Even if a PE were alleged under aggressive interpretation, the statutory exemption in Schedule IV would override the domestic chargeability, providing tax certainty that treaties often fail to deliver due to interpretive litigation.

Further, there has been immense litigation on whether payments for cloud services or bandwidth constitute "Royalty" for the "use of equipment." While courts (e.g., in Microsoft Regional Sales Pte Ltd and MOL Corporation) have held that cloud subscriptions are not Royalty under treaties as they do not involve the transfer of copyright or control over equipment, domestic law (Finance Act 2012 amendments) retrospectively expanded the definition of Royalty to include transmission by satellite/cable and software use,.

The 2047 holiday bypasses this characterization debate entirely. Whether the income is characterized as Business Income (attributable to PE) or Royalty (for equipment use), it is exempt under Schedule IV.

The Transfer Pricing Angle: 15% Safe Harbour

The Budget Speech (Para 131) announce a corollary benefit: A Safe Harbour of 15% on cost where the Indian data centre provider is a related entity. Transfer Pricing disputes in the IT/ITeS sector are rampant. The Safe Harbour Rules generally prescribe margins for IT-enabled services (ITeS) or contract R&D ranging often between 17% to 24% depending on transaction values and service types.

By setting a 15% cost-plus mark-up, the government is offering elimination of rigorous TP audits for the Indian entity. A 15% mark-up is generally lower than the median margins (20%+) often demanded by Transfer Pricing Officers (TPOs) for high-end infrastructure services.

This ensures that the Indian subsidiary (operating the data centre) pays a guaranteed tax on its cost-plus revenue, while the foreign parent enjoys tax-free status on the surplus revenue generated from end-customers.

The Data Centre Tax Holiday Scheme is a strategic maneuver to position India as a global data hub. It skillfully navigates the complexities of Significant Economic Presence and Permanent Establishment risks by creating a domestic exemption that overrides the physical nexus rule. By forcing Indian sales through local resellers, it protects the domestic tax base, and also 15% safe harbour minimizes litigation and is quite attractive rate compare to current ongoing litigations on ITeS.

Note: this article originally published on taxmann.com: [2026] 183 taxmann.com 68 (Article)