From “Necessary Evil” to “Fiscal Morality”: The Global Evolution of Anti-Abuse Laws and the Indian Context

From “Necessary Evil” to “Fiscal Morality”: The Global Evolution of Anti-Abuse Laws and the Indian Context

This article is organized into three distinct sections:

- Part A: This section discuss the evolution of Indian tax jurisprudence over the last two decades from Azadi Bachao Andolan (2003) to Tiger Global International II Holdings (2026)

- Part B: Global Jurisprudence – A comprehensive review of landmark judicial pronouncements and anti-avoidance doctrines from around the world.

- Part C: The New Normal – A practical guide for taxpayers navigating the current regulatory environment, contrasting the legal frameworks of India with those of various international jurisdictions.

Part A - From "Necessary Evil" to "Fiscal Morality" in Indian Context

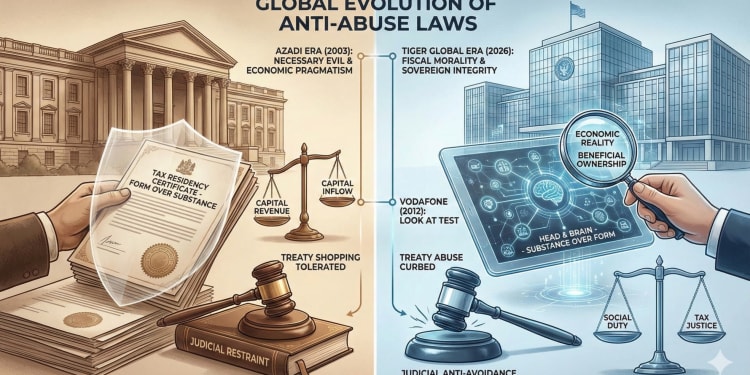

The journey of Indian tax jurisprudence over the last two decades, bookended by the Supreme Court’s rulings in Union of India v. Azadi Bachao Andolan (2003) and The Authority for Advance Rulings v. Tiger Global International II Holdings (2026), represents a profound transformation in the judicial philosophy of the state. It marks a transition from economic pragmatism, where treaty shopping was tolerated as an incentive for investment, to fiscal morality, where tax avoidance is viewed as a violation of sovereign rights and social duty.

"Necessary Evil" vs. "Fiscal Morality"

The Azadi Era (2003): The Doctrine of Economic Pragmatism

In 2003, India was a developing economy hungry for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The Supreme Court in Azadi Bachao Andolan adopted a philosophy of judicial restraint driven by economic necessity. The Court explicitly acknowledged that while treaty shopping might result in revenue loss, it was a "necessary evil" tolerated by developing countries to attract scarce foreign capital and technology.

Relying on the Duke of Westminster principle, the Court held that a taxpayer is entitled to arrange their affairs to minimize tax. It famously stated, "There is nothing like equity in a fiscal statute," and rejected the notion that "treaty shopping is unethical and illegal" merely because the revenue perceives a loss. The Court held that if a company was validly incorporated in Mauritius and held a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC), the "form" of the transaction must be respected.

In that era, the motive of tax avoidance was considered irrelevant to the legality of the structure. The Revenue was precluded from "lifting the corporate veil" to check if the Mauritius entity was merely a shell company controlled from elsewhere. This created a "golden route" for investments into India, tax-proofed against capital gains

The ‘Vodafone’ Interlude (2012): The "Look At" Test

The next major milestone was Vodafone International Holdings BV v. Union of India (2012). While the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the taxpayer regarding the non-taxability of indirect transfers under the then-existing law, it laid down crucial tests for the future. The Revenue must look at the transaction holistically rather than dissecting it. The Court affirmed that while tax planning is permissible, the corporate veil can be lifted if the structure is a "sham," "fraud," or a "colourable device" used to evade tax.

Following Vodafone, the Finance Act, 2012, amended Section 9(1)(i) retrospectively to tax "indirect transfers"—where shares of a foreign company derive substantial value from assets in India.

The Tiger Global Era (2026): The Doctrine of Sovereign Integrity

By 2026, the global and domestic landscape had shifted toward the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) consensus. In Tiger Global, the Supreme Court dismantled the Azadi logic, replacing it with a philosophy of substantive justice.

In a striking philosophical pivot, Justice Mahadevan (and concurring Justice Pardiwala) declared, "It is high time for the judiciary in India too to part its ways from the principle of Westminster and the alluring logic of tax avoidance". Quoting Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Court re-framed taxation not as a burden to be minimized, but as a moral sanction required for a Welfare State. It observed that avoiding tax is "not unethical" is a pretence; in a modern welfare state, financial needs backed by law must be respected. The Hon’ble Supreme Court ruled that the "mere holding of a TRC cannot, by itself, prevent an enquiry." The judiciary must now "look through" the legal form to find the "head and brain" of the company. If the real control lies in the USA (as with Mr. Coleman in this case), the Mauritian entity is a "colorable device" regardless of its valid incorporation.

A central pillar of the judgement, expounded extensively by Justice Pardiwala, is the reassertion of the nation-state’s inherent power in an era of globalization. The judgement posits that the power to levy and collect tax is an inherent sovereign function, circumscribed only by the requirement of legal authority. Justice Pardiwala observes that in the modern world, sovereignty is no longer confined to territorial boundaries but extends to "economic sovereignty," which is susceptible to external pressures and geo-political climates.

The Court acknowledges a philosophical tension—or a "tightrope walk"—between making a nation attractive for foreign investment and protecting the core objectives of its people. The ruling rejects the notion that developing nations must compromise their sovereign right to tax income arising within their borders merely to attract capital.

The judgement challenges the philosophy that treaties are static, fossilized bargains. It argues that carrying the "burden or legacy of formative years" of treaty-making is inappropriate when global trade dynamics have surged ahead. Instead, the Court advocates for a "contextual and meaningful interpretation" that makes treaties vibrant and relevant to current economic realities, asserting that "retention [of sovereignty] should be the golden rule, and yielding should be an exception".

The judgement revives the moral dimensions of taxation, explicitly pivoting back to the philosophy of Justice O. Chinnappa Reddy in McDowell & Co. Ltd. (1985), which had been diluted by Azadi Bachao Andolan (2004) and Vodafone (2012). Quoting Justice Chinnappa Reddy, the Court reiterates that taxes are the price paid for civilization. It rejects the Libertarian view (often associated with the Duke of Westminster principle) that tax avoidance is a game of wits or that a taxpayer is entitled to arrange affairs solely to minimize tax.

The Court asserts that there is a moral sanction behind tax laws and declares it a "pretence" to suggest that tax avoidance is not unethical. It posits that a welfare state cannot afford the luxury of "alluring logic of tax avoidance" when it has constitutional duties to its people.

By validating the "Judicial Anti-Avoidance Rule" (JAAR), the Court establishes that the judiciary has a duty to expose "sophisticated legal devices" and refuse them judicial benediction,. The judgement implies that legal form cannot be used as a mask for "fraudulent or fictitious" transactions designed solely to defeat public revenue.

Legal Realism: The "Head and Brain" vs. The "Paper Shield"

Epistemologically, the judgement shifts from a "formalist" view—where documents create reality—to a "realist" view—where facts determine legal status.

In a significant departure from Azadi Bachao, the Court strips the Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) of its status as conclusive proof. It characterizes the TRC as "decisive, ambiguous and ambulatory," merely recording "futuristic assertions without any independent verification".

The Court prioritizes the metaphysical concept of the "Head and Brain" (control and management) over the physical fact of incorporation. It argues that if the directing mind of a company is situated in the USA, a Board of Directors in Mauritius acting as mere "puppets" cannot establish residency.

The judgement reinforces the doctrine that the corporate veil is a privilege, not an absolute right. It holds that the veil must be pierced when a structure is a "sham," "colorable device," or used for tax evasion. The Court looks past the "legal facade" to the "economic realities," ruling that a transaction without commercial substance (other than tax avoidance) is a fiscal nullity.

Certainty vs. Justice

Finally, the judgement addresses the tension between the legal virtue of "certainty" (often demanded by investors) and the virtue of "justice" (demanded by the State). While acknowledging that certainty is integral to the rule of law and crucial for foreign investors, the Court rules that certainty cannot be purchased at the cost of abuse. The "mere holding of a TRC" cannot prevent an enquiry if the entity is established as a device to avoid tax. The judgement also implies that legal certainty is not static; as methods of tax evasion evolve, so too must the "emerging techniques of interpretation" used by the Courts to counter them. The Court concludes that the State must evolve new ways of tapping revenue and checking evasion, provided it stays within the authority of law.

In sum, the Tiger Global (2026) judgement represents a philosophical reclamation of the state's moral and sovereign right to tax real economic value, declaring that the "form" of a transaction can no longer hold the "substance" of the law hostage.

Comparative Analysis of Legal Evolution

|

Feature |

Azadi Bachao Andolan (2003) |

Tiger Global (2026) |

|

Role of TRC |

A TRC issued by Mauritius is sufficient evidence of residence and beneficial ownership. The Revenue cannot go behind it. |

TRC is "non-decisive, ambiguous and ambulatory." It is an eligibility condition, not a final proof. The Revenue can pierce the veil. |

|

Treaty Shopping |

Viewed as a legitimate incentive for FDI. A resident of a third country can route investment through a treaty partner. |

Viewed as "Treaty Abuse." Treaties are meant to prevent double taxation, not facilitate "double non-taxation" or tax evasion. |

|

Tax Avoidance |

Unless it is a sham, legitimate tax planning within the framework of law is allowed. Motive is irrelevant. |

"Colourable devices" and structures with no commercial substance other than tax avoidance are struck down under GAAR/JAAR. |

|

Interpretation of Tax Treaty |

If the treaty does not have a Limitation of Benefits (LOB) clause, the Court cannot invent one. |

Even without a specific LOB for the relevant period, the "object and purpose" of the treaty (prevention of evasion) allows the denial of benefits. |

The Drivers of Evolution: Why the Shift?

The Tiger Global judgment is not just a reversal of legal precedent; it is a judicial ratification of two decades of legislative aggression.

- Legislative Override (The Vodafone Effect): The Tiger Global judgment explicitly relies on the legislative amendments made post-2012 (Section 9(1)(i) indirect transfers, GAAR, Section 90(2A)). The Court noted that Parliament has the power to "remove the basis of a judicial decision" (referring to Vodafone and Azadi). The 2003 judgment operated in a pre-GAAR era; the 2026 judgment enforces the legislative will to curb "impermissible avoidance arrangements".

- Global Consensus (BEPS): The 2003 judgment relied on older international law principles (like Lord McNair's views) that permitted treaty shopping. The 2026 judgment aligns with the post-BEPS world order, citing the 2016 India-Mauritius Protocol which was specifically amended to "shut the back door" of tax avoidance and round-tripping.

- The "Head and Brain" Test: The Court has moved from a "legal" test of residence (incorporation) to a "commercial" test. In Tiger Global, the fact that the "head and brain" (Mr. Coleman) was in the USA and not Mauritius was decisive. The Court found the Mauritian board was merely "signing off" on decisions made elsewhere, reducing the entity to a conduit.

Part B - The Evolution of Anti Abuse Law Across the Globe

United States

- Gregory v. Helvering (1935): The US Supreme Court held that while taxpayers have a legal right to decrease their taxes, a transaction that has no business purpose and is a mere contrivance to escape taxation will be disregarded. The Court ruled that to hold otherwise would "exalt artifice above reality”

- Aiken Industries Inc. v. Commissioner (1971): The US Tax Court denied treaty benefits for interest payments made to a Honduran company because it was a mere conduit for a Bahamian parent. The Court interpreted the treaty term "received by" to require dominion and control, establishing that back-to-back loans lacking economic substance could be disregarded.

- Moline Properties, Inc. v. Commissioner (1943): The Supreme Court held that a corporate form should not be disregarded if there was a valid business purpose for its formation or if it engaged in substantive business activity.

- Knetsch v. United States (1960): A key decision regarding the "sham transaction" doctrine, where the Court disallowed deductions for interest payments in a transaction that did not appreciably affect the taxpayer’s beneficial interest except to reduce tax.

- Johansson v. United States (1964): The court denied treaty benefits to a Swiss corporation set up by a Swedish boxer, ruling that the entity had no legitimate business purpose and was a mere conduit for the individual’s personal services income.

United Kingdom

- IRC v. Duke of Westminster (1936): This case established the principle that "every man is entitled if he can to order his affairs so that the tax attaching... is less than it otherwise would be." It historically prioritized legal form over economic substance.

- W.T. Ramsay v. IRC (1982): A pivotal case that introduced the "Ramsay principle" (or fiscal nullity doctrine). The House of Lords held that the court can look at a series of pre-ordained transactions as a whole and disregard steps inserted solely for tax avoidance purposes.

- Indofood International Finance Ltd v. JP Morgan Chase Bank (2006): The Court of Appeal denied treaty benefits, ruling that an interposed Dutch company was not the beneficial owner of interest because it had no practical dominion over the income, effectively acting as a conduit.

- IRC v. Commerzbank AG (1990): In this case, the court applied the natural and ordinary meaning of the treaty text, even though it resulted in treaty benefits (exemption) for residents of third states (Brazil and Germany) under the UK-US treaty.

If the law has a hole in it, Commerzbank case says you can walk through it. However, modern law, says that if you walk through that hole just to avoid tax, you’ve committed an "Abuse of Rights."

European Union (CJEU)

- Halifax plc (2006): A landmark VAT decision where the CJEU established that EU law prohibits "abusive practices." It held that transactions can be disregarded if their essential aim is to obtain a tax advantage contrary to the purpose of the relevant legislation. The court ignored the subsidiaries and treated the construction as if the builder had billed the bank directly. Halifax was forced to pay back the millions in "extra" VAT refunds they had claimed.

- Cadbury Schweppes (2006): This case defined the limits of Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) rules within the EU. The Court ruled that anti-abuse provisions restricting the freedom of establishment are only justifiable if they target "wholly artificial arrangements" that do not reflect economic reality. The Court held that a tax motive (wanting to pay 10% instead of 30%) is not enough to justify a tax penalty. To be "artificial," the subsidiary must be a "letterbox" or "front" company.

- The "Danish Beneficial Ownership Cases" (2019) (N Luxembourg 1 and T Danmark): In both cases, a Danish company paid large sums (interest in N Luxembourg 1 and dividends in T Danmark) to a holding company in another EU member state (like Luxembourg or Cyprus). Those EU holding companies were, in turn, owned by entities in non-EU tax havens or private equity funds. The CJEU ruled that the prohibition of abuse of rights is a general principle of EU law. Member States must deny treaty or directive benefits in cases of fraud or abuse (such as using conduit companies) even in the absence of specific domestic or treaty anti-abuse provisions.

Canada

- Canada Trustco Mortgage Co. v. Canada (2005) & Mathew v. Canada (2005): These are the seminal Supreme Court decisions interpreting the Canadian GAAR. The Court established a three-part test: (1) a tax benefit, (2) an avoidance transaction, and (3) abusive tax avoidance (misuse or abuse of the provisions of the Act). The burden of proving abuse lies with the Minister. Canada Trustco is the case important because it tells the government: You can't use the GAAR just because a taxpayer was clever. You have to prove they broke the spirit of the law, not just your budget.

- Prévost Car Inc. v. The Queen (2008/2009): The courts held that a Dutch holding company was the beneficial owner of dividends because it had possession, use, and risk of the funds, and was not merely an agent or conduit, despite being owned by non-treaty residents. The CRA argued that since the money factually flowed straight through to the parents, the Dutch company wasn't the owner. The Court disagreed the CRA’s arguments and held that Unless there is a legal or contractual obligation to pay the money to someone else (like an agent or a nominee), the company remains the beneficial owner. Even if the Dutch company usually paid the dividends to its parents, it legally could have used the money to pay its own creditors or invest in a new venture. Because it had that legal discretion, it wasn't a conduit.

- Velcro Canada Inc. v. The Queen (2012): Followed the Prévost decision, affirming that a contractual obligation to pay funds to a third party does not automatically negate beneficial ownership unless the recipient is a mere administrator or agent. Even though the vibe of the deal was clearly tax-driven, the legal form was a series of valid contracts that the court felt obligated to respect. The TCC ruled in favor of Velcro Canada. The judge applied the "Prévost test" and found that VHBV met all the requirements of a beneficial owner.

- Stubart Investments Ltd. v. The Queen (1984): The Supreme Court rejected a strict "business purpose" test. The Court held that a transaction cannot be disregarded solely because it lacks a "bona fide business purpose." If the law allows you to transfer assets, and you legally transfer them, the court won't stop you just because you did it to save money. In 1988, the GAAR was introduced in the law specifically to override the Stubart decision.

India

- McDowell & Co. Ltd. v. CTO (1985): A landmark ruling where the Supreme Court held that tax planning is legitimate, but "colourable devices" and subterfuges to evade tax are not. It signaled a shift towards looking at the substance of transactions.

- Azadi Bachao Andolan (2003): The Supreme Court upheld "treaty shopping" (specifically via Mauritius), stating it was not illegal unless prohibited by a Limitation of Benefits (LOB) clause. It reaffirmed the Westminster principle that taxpayers can arrange affairs to minimize tax.

- Vodafone International Holdings BV (2012): The Supreme Court held that the tax department must "look at" the transaction as a whole rather than "look through" it. It ruled that in the absence of a statutory GAAR, the legal form of a transaction (share transfer) must be respected unless it is a sham.

- Tiger Global International II Holdings (2026): A recent Supreme Court judgment that set aside the Azadi Bachao doctrine. It ruled that a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) is not conclusive proof of residence if there is evidence of tax avoidance. The Court emphasized that treaties are intended to prevent double taxation, not facilitate double non-taxation, and applied a "substance over form" approach to deny benefits to a conduit company.

Australia

- Newton v. Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1958): The Privy Council applied a "predication test," stating that if an arrangement can only be explained by the purpose of avoiding tax, it may be disregarded.

- Federal Commissioner of Taxation v. Hart (2004): The High Court considered the definition of a "scheme" and "tax benefit" under the statutory GAAR (Part IVA), taking a broad view of what constitutes a tax avoidance scheme.

- Virgin Holdings SA (2008): The court ruled that Australia's anti-avoidance rules (Part IVA) could still apply even if a treaty seemingly protected the taxpayer. It confirmed that taxpayer can't use a tax treaty as an "impenetrable shield" if the underlying transaction is deemed to be a scheme designed primarily for tax benefits.

Undershaft (2009): Undershaft was a company incorporated in the UK, part of a global group. The Australian Tax Office (ATO) argued that Undershaft was actually an Australian resident because its "central management and control" (CM&C) was located in Australia. The court sided with Undershaft. They held that as long as the board of directors actually met, considered the matters, and made the decisions, the CM&C stayed where the board sat. The court noted that even if the directors followed the "suggestions" of a parent company in Australia, they were still the ones exercising the legal power to act. “Influence” from abroad does not equal "control" from abroad.

Other Jurisdictions

- Switzerland: A Holding ApS (2005) – The Federal Supreme Court held that treaty benefits could be denied under the "abuse of rights" doctrine even without a specific anti-abuse provision in the treaty, particularly in treaty shopping scenarios involving conduit companies.

- Argentina: Molinos Rio de la Plata (2021) – The courts applied the domestic "economic reality" (substance over form) principle to disregard a Chilean holding company and deny treaty benefits, viewing it as a conduit.

- South Korea: Mando case – The Supreme Court applied the substance-over-form principle to disregard an interposed Dutch company and attribute income to the substantive owners, denying treaty benefits,.

- New Zealand: Ben Nevis Forestry Ventures Ltd v. Commissioner (2009) – a.k.a. "Trinity Case": A seminal Supreme Court decision on the statutory GAAR, establishing that the "parliamentary contemplation" test is used to determine if a tax avoidance arrangement exists. The Supreme Court of New Zealand ruled in favor of the Commissioner (the Government). They established a two-step test for tax avoidance: Step 1: The Specific Provision. Did the taxpayer follow the literal words of the law? (In this case, yes—the laws for forestry and depreciation technically allowed these deductions). Step 2: Parliamentary Contemplation. Even if you follow the words, did you use them in a way that Parliament never intended?

- Netherlands: Royal Dutch Shell (1994): In the landmark Royal Dutch Shell (1994) case (Case No. 28 638), the Dutch Supreme Court (Hoge Raad) delivered a pivotal ruling on the international tax concept of "beneficial ownership" that remains a cornerstone of legal formalism today. The case involved a Luxembourg company that sold dividend coupons from its Shell shares to a UK stockbroker just before the dividends were paid; because the Luxembourg entity lacked treaty benefits, it faced a 25% withholding tax, whereas the UK broker claimed a reduced 15% rate under the UK-Netherlands treaty. The Dutch tax authorities challenged the 10% refund, arguing the broker wasn't the "beneficial owner" since it didn't own the underlying shares and the transaction was a clear case of "dividend stripping." However, the Court ruled in favor of the taxpayer, holding that the broker was indeed the beneficial owner because it had the legal title to the coupons and "free disposal" of the income, meaning it was under no legal obligation to pass the money to a third party. This decision established that, in the Netherlands, beneficial ownership is determined by legal and contractual rights rather than economic "substance" or the identity of the shareholder, effectively permitting dividend stripping structures until specific anti-abuse legislation was later enacted.

Part C - The "New Normal"

The evolution of the Indian judiciary can be summarized as a movement from facilitator to guardian. In 2003, the Court acted as a facilitator of international trade, prioritizing certainty and capital inflow over strict tax enforcement. In 2026, the Court views itself as the guardian of the "economic interests of the nation". The Tiger Global judgment establishes that in the modern era, Tax Sovereignty is paramount. The "double non-taxation" enjoyed by foreign investors under the Azadi regime has been effectively ended. The judiciary has signaled that while taxpayers are free to plan their affairs, they cannot use "artificial arrangements" that exist only on paper to defeat the intent of the Welfare State.

Further, based on the evolving landscape of international taxation—marked by the implementation of BEPS Action Plans, the Multilateral Instrument (MLI), the introduction of General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR) in domestic laws, jurisprudence across a globe and the landmark Supreme Court judgment in Tiger Global International II Holdings (2026)—taxpayers must now satisfy a rigorous "substance over form" standard to avail tax treaty benefits.

The mere possession of a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) is no longer a "golden ticket" to treaty protection. To secure treaty benefits going forward, taxpayers must ensure compliance with the following checklist:

- Establish Commercial Substance (Beyond Paper Presence)

The Supreme Court in Tiger Global clarified that a TRC is merely an eligibility condition, not conclusive proof of residence. To withstand scrutiny, the entity must prove it is not a "shell" or "conduit."

- Physical Presence: The entity should have its own office space, equipment, and qualified employees in the residence state commensurate with its business activities.

- Independent Decision Making: The entity’s Board of Directors must exercise independent discretion. Decisions should not be "rubber-stamped" instructions from a parent company or beneficial owner in a third country. The "head and brain" of the company must be demonstrably situated in the residence state.

- Operating Expenses: The entity should incur logical administrative and operating expenditures in its state of residence (e.g., salary, rent, statutory fees).

- Demonstrate Beneficial Ownership

For claiming reduced withholding tax rates on passive income (dividends, interest, royalties), the recipient must be the beneficial owner, not just the legal titleholder.

- Control over Income: The recipient must have the full right to use and enjoy the income unconstrained by a contractual or legal obligation to pass that payment on to another person.

- Avoid Conduit Status: If the entity acts as a mere agent, nominee, or conduit that channels funds to a third party, treaty benefits will be denied.

- Documentation: Maintain evidence that the entity assumes risks (e.g., credit risk, exchange risk) and has the capacity to satisfy the "dominion and control" test over the assets generating the income.

- Satisfy the "Principal Purpose Test" (PPT)

Under the MLI (BEPS Action 6), treaty benefits are denied if one of the principal purposes of the arrangement or transaction was to obtain that benefit.

- Business Rationale: The taxpayer must demonstrate a bona fide commercial reason for the structure (e.g., access to skilled labor, regulatory environment, regional headquarters) other than tax avoidance.

- Documentation of Intent: Maintain contemporaneous documentation (emails, board minutes, feasibility studies) showing that commercial factors drove the decision to incorporate or invest through that specific jurisdiction.

- Meet "Limitation of Benefits" (LOB) Requirements

Many modern treaties (e.g., India-US, India-Singapore) and the MLI contain objective LOB clauses. Taxpayers must fall into specific categories, such as:

- Publicly Traded: The entity’s shares are regularly traded on a recognized stock exchange in the residence state.

- Active Trade or Business: The entity is engaged in an active trade or business in the residence state, and the income from the source state is connected to that business.

- Ownership/Base Erosion Test: At least 50% of the entity is owned by qualified residents, and less than 50% of its gross income is paid out as tax-deductible payments (interest/royalties) to non-residents.

- Prove "Liability to Tax" in the Residence State

Taxpayers must prove they are "liable to tax" in the residence state by reason of domicile, residence, or place of management.

- Subject to Tax vs. Liable to Tax: In treaties with a "subject to tax" clause, the income must actually be taxed in the residence state. If the income is exempt in the residence state, treaty benefits in the source state may be denied.

- Fiscal Domicile: Ensure the entity is not considered a dual resident. If dual residency exists, the tie-breaker rule (often decided by Competent Authorities under the MLI) determines the single state of residence.

- Compliance with Statutory Documentation (Domestic Law)

In India, specifically, Section 90(4) and (5) of the Income-tax Act mandate specific filings,:

- Tax Residency Certificate (TRC): Obtain a valid TRC from the government of the residence country.

- Form 10F and Declaration: File Form 10F electronically if the TRC does not contain all prescribed particulars (e.g., Tax ID, address, period of validity). Further, it is advisable to obtain a comprehensive declaration from the non resident.

- Form 15CA/CB: Ensure the payer furnishes these forms for remittances, certifying the nature of payment and applicable treaty rates.

- Awareness of GAAR (General Anti-Avoidance Rules)

Even if specific treaty rules (LOB) are met, domestic GAAR can override the treaty if the arrangement is deemed an "impermissible avoidance arrangement".

- Grandfathering Limits: While investments made before April 1, 2017, may be grandfathered under specific treaties (like India-Mauritius), the Tiger Global judgment suggests that "colorable devices" or "sham" structures may still be scrutinized under judicial anti-avoidance rules regardless of grandfathering dates.

- Substance Test: GAAR looks at whether the arrangement lacks commercial substance, creates abnormal rights/obligations, or is not at arm's length.

The evolution of Indian international tax jurisprudence over the last two decades presents a profound narrative of reversal, bookended by a singular legal thread: the presence of Sr. Advocate Mr. Harish Salve. It is a striking historical irony that the same legal titan who, as Solicitor General, successfully defended the sanctity of the Mauritius route and the conclusiveness of the Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) in Azadi Bachao Andolan (2003), and later persuaded the Supreme Court to prioritize the "look at" form over the "look through" substance in the landmark Vodafone victory (2012), stood once again at the lectern for the respondents in Tiger Global (2026). However, this time, he witnessed the judiciary dismantle the very fortress of "form over substance" he had helped construct, with the Supreme Court explicitly rejecting the "alluring logic of tax avoidance" that had prevailed for twenty years. This jurisprudential full circle signifies that while the master advocate remained constant, the economic philosophy of the nation shifted tectonically beneath him—moving from an era where treaty shopping was tolerated as a "necessary evil" for capital importation to a new age of "fiscal morality" where the sovereign right to tax real economic substance overrides the most expertly crafted legal structures.

Note: the above article originally published on taxmann.com: [2026] 182 taxmann.com 756 (Article)