Navigating the Complexities of Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) for DTAA Benefits

Introduction:

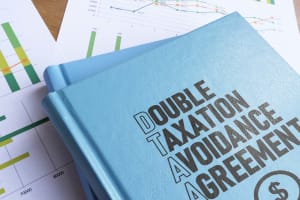

Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements (DTAA) play a significant role in international taxation, aiming to prevent the double taxation of income earned by taxpayers in two different countries. However, the requirement of a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) for claiming DTAA benefits has become a subject of legal complexities and practical challenges. In this article, we will delve into the various aspects surrounding TRCs, including their differentiation from other registration certificates, the legal issues surrounding Section 90(4) of the Income Tax Act, the absence of TRC provisions in India's DTAA agreements, and the implications for businesses.

TRC vs. Incorporation Certificate and Other Registration Certificates:

It is crucial to clarify that a TRC cannot be equated with an incorporation certificate or any other registration certificates. The provision stated in Section 90(4) of the Income Tax Act explicitly mandates the production of a TRC, along with other relevant information (in Form 10F), for claiming DTAA benefits. While obtaining a TRC can be challenging, especially for individuals, it is vital to comply with the law's mandate.

Legal Issues Surrounding Section 90(4):

One of the key legal issues arises from the potential contradiction between Section 90(4) and Section 90(2) of the Income Tax Act, as well as various judgments of the High Court, including the Supreme Court. These judgments establish that, in case of conflict between the Income Tax Act and the provisions of the DTAA, the provisions of the DTAA should prevail. This raises questions about the absolute necessity of a TRC as mandated by Section 90(4).

Skaps Industries India Pvt Ltd vs ITO, International Taxation, Ahmedabad ITAT

In this case, the ITAT held that Section 90(2) of the Income Tax Act, 1961 in India provides a unique and unqualified "treaty override" provision. This means that regardless of the provisions in the Income Tax Act, if a person is covered by an agreement under Section 90(1), the provisions of the Act will only apply to the extent that they are more beneficial to the taxpayer. The Act cannot impose a greater burden on the taxpayer than what is specified in the applicable tax treaty.

However, the only limitation to this unqualified treaty override provision is that the provisions of Chapter X-A, which deals with the General Anti Avoidance Rules, will apply to the taxpayer even if they are not beneficial. This exception is stated in Section 90(2A), which is the only provision in the Income Tax Act, 1961 that starts with a non-obstante clause in relation to Section 90(2). Therefore, it is the only restriction on the superiority of tax treaty provisions over the provisions of the Indian Income Tax Act, 1961.

ITAT also observe that:

8. In the light of our this analysis, when we turn to Section 90(4), as indeed other sub sections of Section 90, we find that these provisions do not start with a obstante clause vis-àvis Section 90(2) and, therefore, these sub sections cannot be construed as limitation to, or rider to, somewhat unqualified treaty override stipulated in Section 90(2). Whatever interpretation one assigns to this sub section, essentially the fundamental approach has to be that this sub section will be applicable only when the same are more beneficial to the assessee vis-à-vis the provisions of the applicable tax treaty; that principle of treaty override, as set out in Section 90(2), remains unaffected by these provisions. As we hold so, we make it clear that whether the same position will also apply with respect to Explanations to Section 90 or not is still an open question, uninfluenced by these discussions, as Explanations to Section 90 may perhaps not have the same legal connotations as the sub sections to Section 90. We leave it that for the time being.

The above decision was also cited and relied by Hyderabad ITAT in the case of Sreenivasa Reddy Cheemalamarri [TS-158-ITAT-2020(HYD)].

A Unilateral Attempt to Deny Treaty Benefits:

Furthermore, Section 90(4) can be seen as a unilateral attempt to deny treaty benefits, potentially conflicting with international law and the principles of reciprocity and mutual benefits that underpin international tax treaties. The timing of the insertion of Section 90(4) through the Finance Act 2012, which came after the conclusion of various DTAA agreements, adds to the complexity and requires careful evaluation.

In the realm of international law, the position on unilateral modification of treaties is guided by the principle of pacta sunt servanda, which means that treaties must be observed and complied with in good faith by all parties involved. This principle serves as the cornerstone of the international legal system and promotes stability, predictability, and trust among nations.

Under customary international law, a treaty can only be modified or terminated by the consent of all parties involved. This principle of consent ensures that the rights and obligations established by a treaty are protected and that no party can unilaterally alter or disregard the provisions of a treaty without the agreement of others.

Unilateral modification of a treaty by one party without the consent of the other parties is generally considered a violation of the treaty and may be viewed as a breach of international law. Unilateral modifications can undermine the integrity of the treaty and erode the trust and confidence among the parties.

Non-Inclusion of Mandatory TRC Requirement in India's DTAA Agreements:

A noteworthy observation is that none of India's DTAA agreements with other countries contain provisions specifically requiring the mandatory submission of a TRC for availing DTAA benefits. If the TRC were universally mandated, it would necessitate countries to enter into agreements clarifying that benefits can only be availed upon producing a TRC. However, the absence of such provisions in the DTAA agreements raises questions about the absolute necessity of a TRC for claiming DTAA benefits.

Navigating the Way Forward:

Considering the legal complexities and practical challenges surrounding TRCs, businesses are advised to make diligent efforts to obtain TRCs from payees. However, in cases where obtaining a TRC is not feasible, businesses must carefully assess the facts and circumstances of each case. This assessment should consider the legal issues discussed earlier, the absence of TRC provisions in DTAA agreements, and the potential risks and consequences of proceeding without a TRC.

It is essential to weigh the available legal avenues and evaluate the potential litigations that may arise from deviating from the TRC requirement. Seeking professional guidance is recommended to ensure compliance with prevailing regulations while balancing the practical challenges faced in obtaining TRCs.

Conclusion:

The requirement of a TRC for claiming DTAA benefits presents businesses with a complex and intricate landscape to navigate. While the legal issues surrounding Section 90(4) and the absence of explicit TRC provisions in India's DTAA agreements raise valid concerns about the essential nature of a TRC, businesses must still endeavor to obtain TRCs whenever possible. In cases where TRCs cannot be procured, a meticulous evaluation of the specific circumstances, coupled with expert guidance, is crucial to making informed decisions that ensure compliance and mitigate potential litigations.